-

Contact us

Contact us

Australian Clearinghouse for Youth StudiesUniversity of Tasmania,

P O Box 5078, UTAS LPO,

Sandy Bay, 7005,

Tasmania, AustraliaTel: (03) 6226 2591Fax: (03) 6226 2578Email: [email protected] -

Search ACYS

- Events

Violence against young women in Australia: Snapshot

By Sheila Allison & Lynette McGaurr

Violence against women refers to ‘any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.’ (United Nations 1993).

Young women are more likely than older women to experience violence

Women in Australia aged 18 to 24 are more likely to experience physical or sexual violence than women in any other age group (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2013). The incidence of sexual assault for women aged 18 to 24 is twice as high as for all women (ABS 2013), while for women aged 15 to 19 it could be as much as four times higher (Tarczon & Quadara 2012).

Percentage of women experiencing sexual assault in the past 12 months

Source: ABS 2013

Women are more likely than men to be injured by domestic violence

Boys, girls, men and women can all behave violently, but ‘women are more likely than men to be injured during domestic violence incidents and to suffer more severe injuries’ (Swan et al. 2008, p.9).

Young women are more likely than young men to experience sexual assault

Sexual assault or rape among young people aged 12 to 20

Source: National Crime Prevention 2001

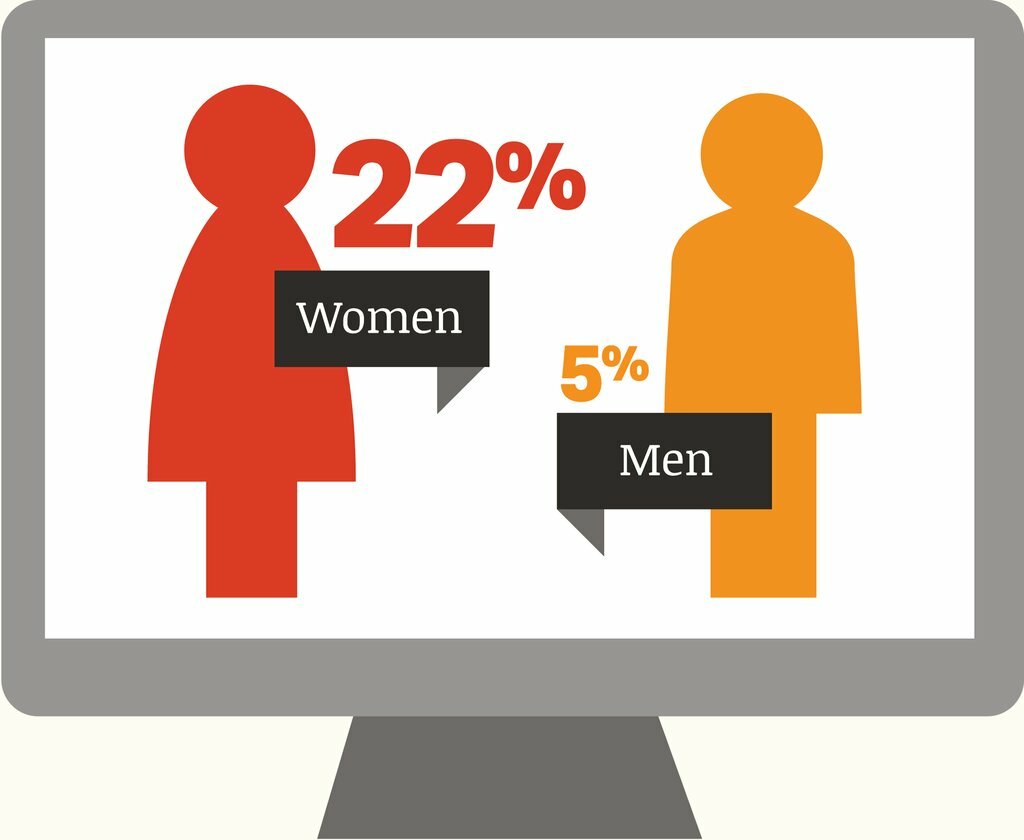

Percentage of women and men aged 18 and over experiencing sexual assault in the past 12 months

Source: ABS 2013

Gender inequality increases the risk

Girls and young women’s risk of violence is heightened by gender inequality such as male-dominated relationships and peer cultures that are sexist, as well as inexperience, age gaps in relationships and lack of access to services (Flood & Fergus 2008).

Young women and gender stereotypes

Girls and young women still suffer sexism and feel pressure to conform to gender stereotypes (Baffour, Kapelle & Smith 2014). Even when young people are able to repeat key anti-violence messages, they do not always apply them in their own intimate relationships (see Sety 2012).

Many young women feel strong social pressure to have a boyfriend and sometimes confuse controlling behaviour with intense love (see Sety 2012). They may also respond to abuse or harassment passively, such as by ignoring it, and be quick to forgive partners who apologise (see Sety 2012).

Young men and gender stereotypes

Young men are much more likely than young women to think that girls want them to take charge in relationships (Cale & Breckenridge 2025a). There is also evidence that the views of their friends are influential in some young men having sex even when they don’t really want to (Mitchell et al. 2014).

The high price of violence against women

Calculating the societal and personal financial costs of violence against women not only adds a powerful dimension to the many other arguments for action but also drives home the scale of the problem. In 2009 the estimated cost to the Australian economy of domestic and non-domestic violence against women and their children in 2008-09 was $13.6 billion (National Council to Reduce Violence against Women and their Children (NCRVWC) 2009, p.34).

Estimated cost to Australian economy of violence against women and their children

Source: NCRVWC 2009

Violence against young women doesn’t only happen at home

The family home is only one of many places where gendered violence occurs and impinges on us all (Orr 2007). Other situations in which young people may encounter gendered violence include their own intimate relationships (dating violence), schools, the workplace, social media and sport.

Young people aged 16 to 25 who think dating violence is common or very common

Source: Cale & Breckenridge 2014a

Experience of sexual harassment in the workplace

Source: Australian Human Rights Commission 2008

Men and boys can be partners in prevention

Primary prevention speaks to us all

Primary prevention aims to prevent violence against women before it occurs and includes strategies directed towards the whole population.

Principles of prevention

We still have much to learn about how best to change gender inequality, gender stereotypes, violence-supportive attitudes and violent behaviour, but our knowledge is increasing all the time. Here are just some of the principles of good practice that studies have found can increase our chances of success (references follow):

Source: Carmody, Salter & Presterudstuen 2014; Dyson & Flood 2008; Flood 2011; Flood & Fergus 2008; Flood & Kendrick 2012; Jewkes, Flood & Lang 2014; Mills 2000; Our Watch 2025b; Sety 2012; VicHealth 2007, 2014; Walden & Wall 2014

- Holistic: Programs should aim to create cultural change across the whole environment (e.g., school, workplace, sporting club etc.).

- Integrated: Programs should be part of a wider strategy that integrates interventions in many forms, at different levels and in a variety of situations.

- Long-term: Programs should engage participants over a long period.

- Flexible: Programs should be adjustable to accommodate different cultures, age groups and/or levels of risk.

- Youth-informed: Programs should be developed and implemented with input from young people.

- Empowering: Programs should empower young women and challenge any misconceptions that dating violence is not serious, is an expression of love or is their own fault.

- Engaged with men and boys: Programs should approach young men as partners in prevention rather than perpetrators and respectfully encourage them to understand and acknowledge the nature of men’s violence against women.

- Safety-conscious: Programs that include ethical bystander approaches should provide clear safety guidelines to participants so that they know how to intervene safely, and understand that they should only intervene when it is safe to do so.

- Trauma-aware: Programs that engage directly with young people must have processes in place to respond appropriately if participants disclose that they have been victims or perpetrators.

- Skilled, resourced and supported: Educators delivering respectful relationships programs and/or the Sex & Ethics Program should be highly trained, adequately resourced, motivated and supported through communities of practice.

- Evaluated: Programs should be accompanied by detailed and long-term evaluation and diligent modification informed by evidence derived from research undertaken specifically with young participants.

(References: Carmody, Salter & Presterudstuen 2014; Dyson & Flood 2008; Flood 2011; Flood & Fergus 2008; Flood & Kendrick 2012; Jewkes, Flood & Lang 2014; Mills 2000; Our Watch 2025b; Sety 2012; VicHealth 2007, 2014; Walden & Wall 2014)

The youth sector is part of the solution

Many young people at risk of being victims or perpetrators of gendered violence are disengaged from formal education, suggesting primary prevention programs in the youth sector may be required to complement those in schools and universities (VicHealth 2007).

Our WATCh (2025b) advises that programs for non-school settings will need to flexible so that they can easily be adapted to different contexts. It also stresses the importance of identifying leaders, peers and mentors who can engage with young people, and notes that training and capacity-building among practitioners will be vital.

Youth workers are also excellently positioned to model and promote gender equity and ethical bystander interventions in their workplaces and day-to-day interactions with young people (see Council of Europe 2007).

See the briefing Violence against women in Australia: Contexts beyond the family home for a full list of references.